The DNA of Emotional Health – Part 4 Should “an Orchid” become “a Dandelion”?

- Home

- Blog

“Illness might progressively vanish, but so might identity. Grief might be diminished, but so might tenderness. Traumas might be erased but so might history. Infirmities might disappear, but so might vulnerability.”

― Siddhartha Mukherjee, M.D.

Dear Reader, last week I began my blog by asking you to consider the feeling of emotional comfort. When we are at ease, our minds are open and kind, joyful and receptive. Our bodies are relaxed and our heartbeat regular. It’s a beautiful feeling—one we likely think of when we consider what it means to feel “happy”. Today, I want to begin by considering this feeling’s exact opposite: a state in which your mind is closed and scared, protective and reactionary—in which your body is tense and your heartbeat racing so fast the blood begins to rush to your face. This, reader, is a state of stress. And while all of us feel it briefly from time-to-time, some individuals are exposed to the harmful effects of stress far more often and for longer periods of time than others and have a harder time escaping its toxic reach. While we may think that we our reaction to stress is under our control, the truth is, we often don’t get much choice in the matter whatsoever—instead, our bodies choose for us. And while we may consciously choose to curtail as many “stressors” in our lives as possible, it is another matter entirely to limit our body’s “stress response” to those remaining stressors. If you remain calm in a stressful environment and find that you can quickly bounce back to a more peaceful state of mind, thank your genes. You’re what I call a “Dandelion”—adaptable, hardy, and capable of surviving and growing almost anywhere. However, if you feel that you’re under a continual onslaught of stress and can barely come up for air before another difficult incident arises, it’s not you—it’s your genes. You’re what I call an “Orchid”—particular contexts may be needed for you to flourish, but once they are present the outcome is stunning.

Orchids are a thing of beauty, but there’s no doubt life is easier if you can grow anywhere. Many individuals who find themselves in a chronic state of stress wish it were otherwise. And here’s the good news—it can be otherwise. What if you could maintain your beautiful orchid personality while also developing a more resilient response to stress? With an understanding of your biology and genetic code, you can Biohack your genes to help you reach that peaceful state of mind with more regularity. It all starts with a simple genetic test.

Fight, Flight or Freeze—How Your Orchid Genes Keep Your Body from the Homeostasis it Covets

We’ve discussed the orchid/dandelion dichotomy on the blog before—but today, I want to take some time to explain why, exactly, your genes may make you more susceptible to stress. While numerous genes play a role in our stress response, three in particular have an outsize impact. I like to call these your “orchid genes”: SLC6A4 S/S, COMT Met/Met, and OXTR G/G.

Your response to stress begins in a part of your brain known as the Amygdala. Located in the center of our brain, the Amygdala scans our environment for images and sounds that may pose a threat. If it finds a “hit”, it immediately triggers another part of our brain, the Hypothalamus, which in turn triggers a “fight-flight-or-freeze” hormonal response along our body’s hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis. The resulting hormonal surge is what we experience as stress.

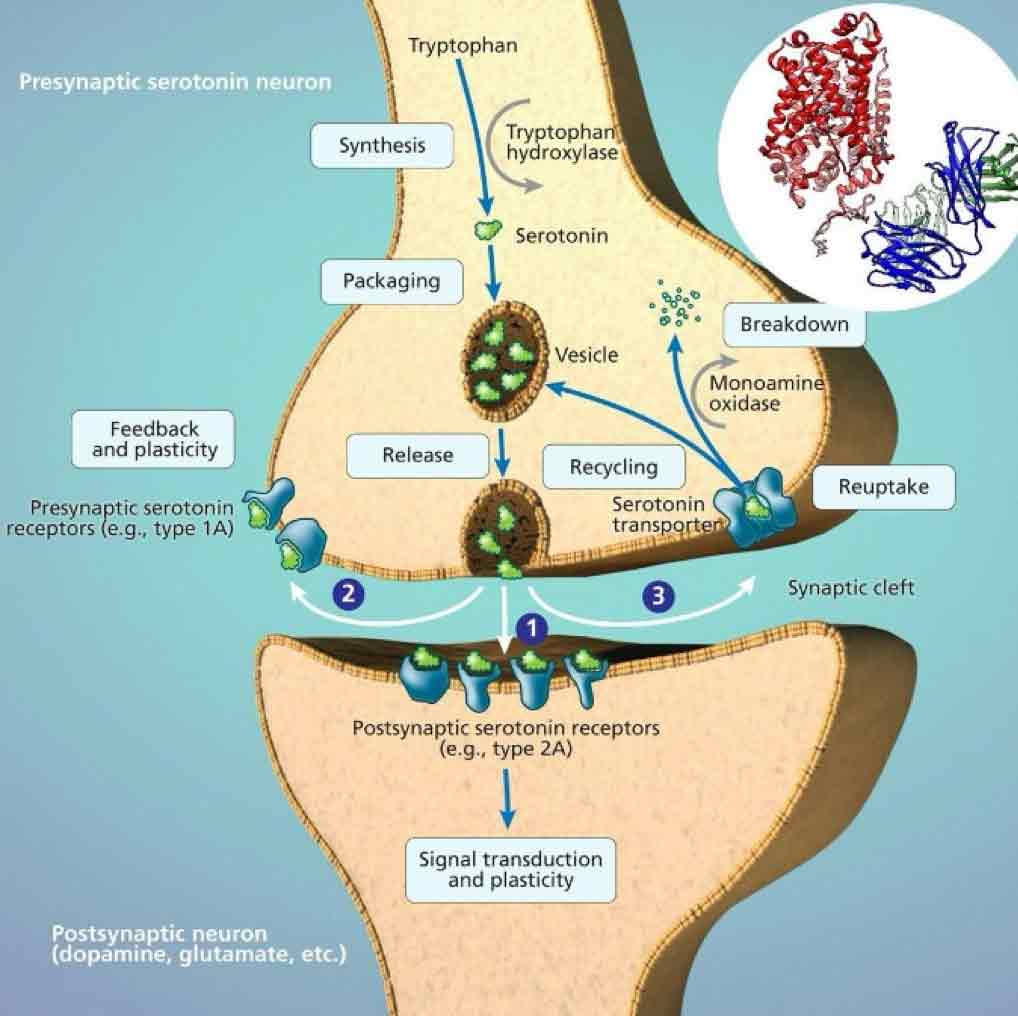

Variants on your orchid genes can impact every stage of this biological process. As we know from prior blogs, our SLC6A4 gene is responsible for regulating our serotonin levels within the synaptic connections that enable brain cells to communicate with each other. Serotonin is a neurotransmitter that helps regulate our sleep, appetite, mood, and anxiety. If you are born with an S/S variant on your SLC6A4 gene, you are genetically predisposed to have fewer serotonin transporters (“reuptake pumps”) that transport serotonin back into the neuron after it is released, as depicted in the image. Under stress, the synapses flood with serotonin and with the S/S variant there are not enough reuptake pumps which results in “flooding” the synapses in the amygdala. This results in excessive activity in the amygdala—creating more “hits” that provoke more fear and anxiety, triggering the aforementioned bodily response.

Variants on your orchid genes can impact every stage of this biological process. As we know from prior blogs, our SLC6A4 gene is responsible for regulating our serotonin levels within the synaptic connections that enable brain cells to communicate with each other. Serotonin is a neurotransmitter that helps regulate our sleep, appetite, mood, and anxiety. If you are born with an S/S variant on your SLC6A4 gene, you are genetically predisposed to have fewer serotonin transporters (“reuptake pumps”) that transport serotonin back into the neuron after it is released, as depicted in the image. Under stress, the synapses flood with serotonin and with the S/S variant there are not enough reuptake pumps which results in “flooding” the synapses in the amygdala. This results in excessive activity in the amygdala—creating more “hits” that provoke more fear and anxiety, triggering the aforementioned bodily response.

COMT regulates a package of neurotransmitters known as the catecholamines— including adrenaline, norepinephrine, and dopamine that are activated at the end of the chain reaction beginning in the Amygdala and moving through the HPA axis. This gene codes for an enzyme that deactivates the stress-inducing catecholamines. If you are born with a Met/Met variant on your COMT gene, your body makes less of that enzyme—which makes it much harder for you to bounce back from a stressful reaction, because your body is slower to deactivate those hormones surging through you.COMT regulates a package of neurotransmitters known as the catecholamines— including adrenaline, norepinephrine, and dopamine that are activated at the end of the chain reaction beginning in the Amygdala and moving through the HPA axis. This gene codes for an enzyme that deactivates the stress-inducing catecholamines. If you are born with a Met/Met variant on your COMT gene, your body makes less of that enzyme—which makes it much harder for you to bounce back from a stressful reaction, because your body is slower to deactivate those hormones surging through you.

Lastly, as we discussed on last week’s blog, your OXTR gene is responsible for regulating oxytocin receptor sensitivity— the receptors that are activated by oxytocin, that wonderful neurotransmitter that facilitates feelings of trust, emotional comfort, and attachment. If you were born with a G/G variant on your OXTR gene, you have plenty of oxytocin receptor sensitivity—and that’s a great thing! However, it also predisposes you to increased activation of the amygdala under certain conditions—for instance, if you are not surrounded by the social support you need to cope more effectively with life stress.

Being born with all three of these genetic variants would translate into your amygdala finding more threats in your environment, and your hypothalamus and HPA axis responding accordingly by pumping out stress hormones with greater frequency and for longer periods of time. In other words—you’re an orchid times three! However, genetic testing gives us the tools to help you Biohack your genetic variants to help you mitigate an overactive stress response. Gina’s story is a perfect example of how to do so.

Gina’s Story: How Biohacking SLC6A4, COMT, and OXTR Variants can Help You Feel Better

Since I began writing about the so-called “orchid genes” whereby one can blossom and flourish in the right environment yet wither and die (emotionally) in the wrong (high stress) environment, several of my “orchid patients” have asked “Dr. Bruce, can you turn me into a dandelion? I really want to become one. I am sick of being an orchid and want to be so much more resilient and want to develop a thick skin. Can we accomplish that with medications and supplements?” Gina* was one such patient.

Gina flew in from LA to see me, at the encouragement of her parents who lived in the DC area. They were terribly worried about her mental health, as she hadn’t been able to work in the past 18 months and had been fired from two prior positions at digital creative marketing agencies. This young adult had already been tried on a series of SSRIs and SNRIs to treat her depression, in combination with Adderall to treat her ADHD, and remained quite depressed and anxious, with executive dysfunction and easy distractibility.

In our first session both of Gina’s parents joined us, and Gina was clearly feeling embarrassed and ashamed. She looked so sad and somewhat frightened, and my heart went out to her and to her worried parents. Her mother, a local gynecologist, broke the ice. “Dr. Kehr, we are here because we see Gina struggling just to get by. Her OCD symptoms are getting worse, and we are afraid that the longer she is out of work the more difficult it will be to secure a new position. And we are concerned that her husband Jim may leave her if she fails to improve, particularly since they need two incomes to afford their lifestyle out there.” Gina’s father, a software engineer, then chimed in, “We have been helping them financially, and luckily are in a position help that way, but Gina’s younger sister is headed off to a private university and before long we ourselves will be under financial strain, can you help us?”

What they most needed was a “leave no stone unturned approach,” combining a personalized, precise method under the biopsychosocial model; a clear game plan moving forward; and a strong measure of hope; and so I said to them, “Gina, I know how hard this must be for you to be here with your parents, having not so long ago been successfully launched into your own independent life, having become financially self-sufficient, and having embarked upon a promising career. And it can be so discouraging to have been tried on multiple medications without feeling much relief. And you may all be feeling scared that this is how you will remain for months or years to come. I promise you I will work as hard as I can to get to the bottom of what’s wrong, and help you begin a treatment plan that leads to recovery.” I then described to them my recommendations that she receive a number of blood studies, and both Professional PGx and Mindful DNA genetic testing assays. And that is how we proceeded. Here is what was uncovered…

Gina had all three “orchid genes”—SLC6A4 S/S, COMT Met/Met, and OXTR G/G—which are associated with overactivation of the amygdala and a larger “fight flight or freeze” response. Additional genetic variants that predisposed her to depression and anxiety were CACNA1C, BDNF and MTHFR. Blood tests revealed the presence of hypothyroidism.

And so we embarked upon a regimen of Trintellix (to address her mood and cognitive symptoms), lithium augmentation to address CACNA1C and BDNF, l-methylfolate to address MTHFR, and a referral to an endocrinologist to address her low thyroid levels.

If You Have Orchid Genes, Context is Critical in Creating Emotional Health or Illness

We then began to explore her work history in the context of her orchid genes and her life-stage developmental challenges. “Gina, at your age there are four huge developmental challenges to overcome and resolve – separate from home, form an identity, establish a career, and find someone to love. You were well on your way to accomplishing all of these when your anxiety and depression began to overwhelm you. Let’s talk about each of these life-stage challenges in the context of you being an “orchid” and understand the relative contributions of each of them, interacting with your orchid genes, that created your emotional distress.” And so we began to explore the stress of leaving behind parents who had been hovering and overprotective, the challenges of falling in love and marrying what sounded like a highly narcissistic man, and the enormous creative deadline pressures she had lived under with her two prior jobs. I then asked her a question and was truly surprised by the answer, “Gina, have you ever engaged in a longer-term psychotherapy to explore and resolve these issues?” As you’ve guessed by now, her answer was “No.”

And so we set about locating for her a psychoanalytic psychotherapist back in LA, and a psychiatrist there who would work with me to further assist Gina in becoming whole.

Tweaking Genes and Altering Context While Preserving Personalities

As to whether we can turn an orchid into a dandelion, the answer is “Why would we ever want to?” Why would we ever want to alter one’s fundamental humanity? While we can help improve one’s resilience through biohacking their personal genome (another way of saying “epigenetically modulate their genes”) and engaging them in psychotherapy, we would never want to alter their fundamental, constitutional sensitivities. One should always remain true to one’s Self.

Gina will never become a Dandelion. But with the right combination of epigenetic influencers, including medication, supplements, psychotherapy, and a less demanding work environment, she will almost certainly become a more resilient Orchid!

.png?width=144&height=144&name=Untitled%20design%20(34).png)